MARCH 2022

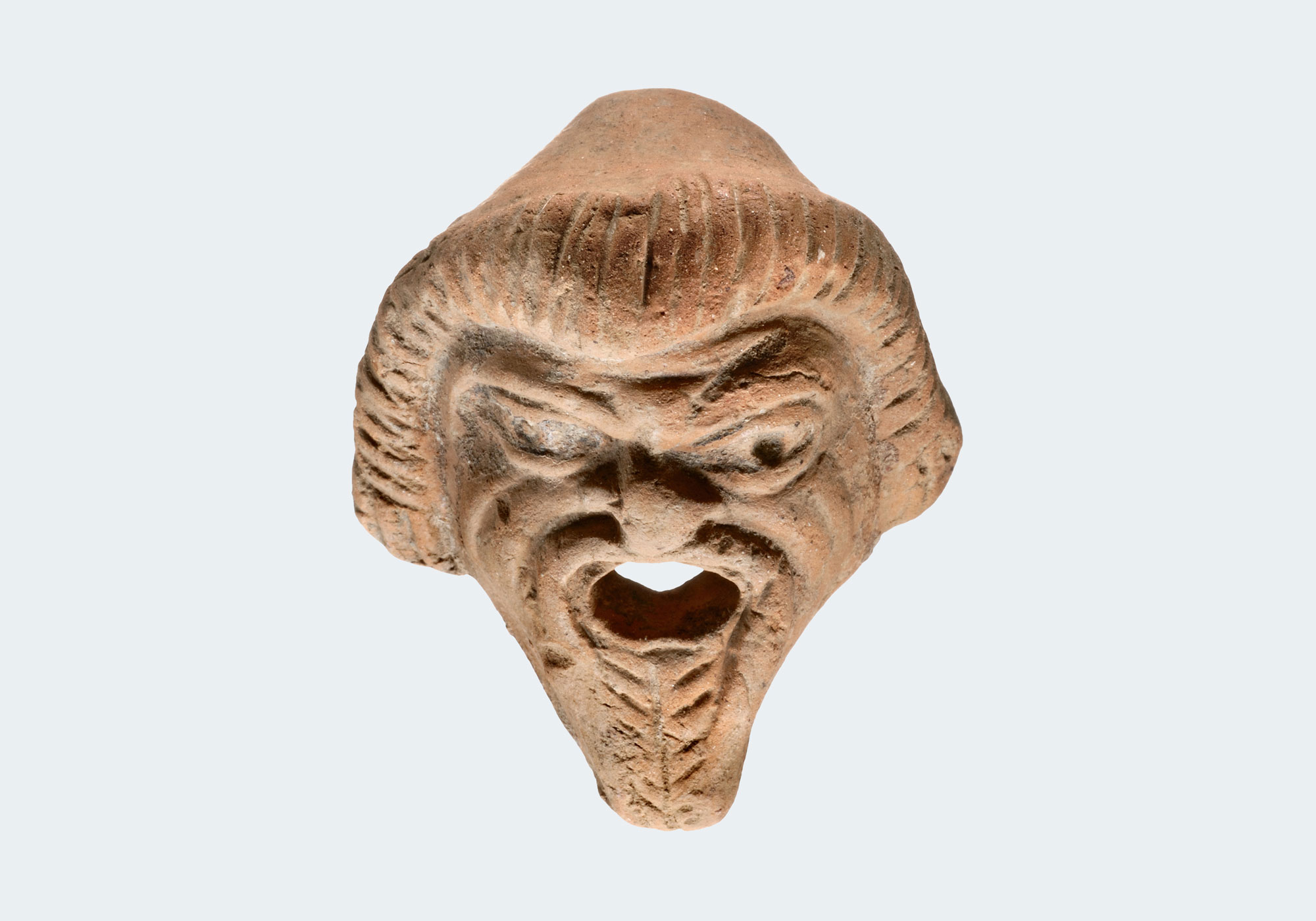

Figurine depicting an actor wearing a theatrical mask.

Roman Period

In 1975, a 5 cm-high clay figurine representing an actor, with only the head remaining intact, was unearthed within Nymphaea, the public fountains situated at Nicopolis’ Western Gate. The actor is adorned with a mask featuring a broad, gaping mouth, defined eyebrows, pronounced wrinkles on the forehead and cheeks, and his mustache and beard are prominently depicted through the engraving.

The mask held a paramount significance in ancient Greek theatrical attire, playing a multifaceted role in enhancing the performance. It not only allowed actors to seamlessly assume multiple roles, both male and female, within the same play but also provided a blank canvas for character portrayal by eliminating distinct individual features.

Polydeukis, as documented in the “Onomastikon,” cataloged a total of 76 distinct facial expressions to correspond with an equivalent number of character archetypes, including the likes of elders, youth, females, slaves, and more.

Their facial expressions were a means of conveying the emotions and qualities of the characters they portrayed. Arched eyebrows signified anger, while downturned brows expressed sorrow. Exaggerated elevation of the eyebrows conveyed the insolence often associated with slaves. Conversely, caution and sincerity were evident in forehead wrinkles. Distinct coloration, with white for females and dark for males, distinguished the genders. The Nicopolis mask, characterized by its coiled hair, prominently arched eyebrows, and furrowed brow, evoked the image of a slave-healer.

The inception of Roman theater dates to the 4th century BC when it emerged as a celebratory dance spectacle within the framework of games (ludi). This is why the Romans referred to it not as theater but as stage competitions (ludiscaenici), which initially didn’t necessitate a dedicated venue. It wasn’t until 55 BC that Rome obtained a permanent theater.

Throughout its development, Roman theater was significantly shaped by the profound influence of ancient Greek drama. Its early written plays, dating back to 240 BC, primarily consisted of translations of Greek tragedies and comedies into Latin. Notably, key figures in Roman theater such as the comedians Plautus and Terentius from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, as well as the tragedian Seneca from the 1st century AD, drew their themes and inspiration from Greek literary works and mythology.

In contrast to the situation in ancient Greece, Roman theater did not primarily revolve around the concerns of Roman citizens. The playwrights themselves often hailed from the lower social strata, remaining detached from political matters. The audience, comprising a diverse mix of men, women, children, and slaves, attended the theater for entertainment rather than to ponder political or profound moral issues. Concurrently, the introduction of new types of spectacles, devoid of educational intent, emerged, such as pantomimes, animal contests, and duels. This trend is also evident in Nicopolis, where a theater was established upon its foundation in 27 BC, and later, in the early 2nd century AD, a conservatory was added to the city’s cultural offerings.

Presently, the actor’s figurine is on display in the initial gallery of the AMN, i.e., the section dedicated to The Roman City

Checkout the exhibit of the month in Collection of the AMN

Ladies and gentlemen, let the show commence!

And with my very first words, I extend my heartfelt wishes for health and happiness to all in the audience.

I present to you Plautus! However, I must clarify, not in my embrace, but I hope to welcome him with open and receptive ears.

Now, I ask for your full attention as I narrate the tale concisely.

Ah, but before I begin, I must not overlook this point:

In their comedies, the playwrights often stress that all the events unfold in Athens, in a bid to infuse a more Greek essence into their work.

However, I shall not deviate from the truth and only speak of where it truly happened.

And one more thing, our production is undeniably Greek, but not of Athenian origin; to be precise, it hails from Sicily.

This prologue introduces the comedy “Menaechmi” by the Latin playwright Plautus (Titus Maccius Plautus, c. 254-184 BC).

[Source: D. Raios, Roman Comedy: Plautus Menaechmi, Traditions, University of Ioannina, 1994]